As my career has come to an abrupt end, it’s healing to look back on all the work I’ve put into this sport. It reminds me of the monumental amount of effort that’s formed the basis of this incredible journey. It helps me to seek pride in what has been, instead of dwelling on what could have been. As I look back into my training logs, patterns emerge. I’d love to share some of my thoughts on what I’ve learned.

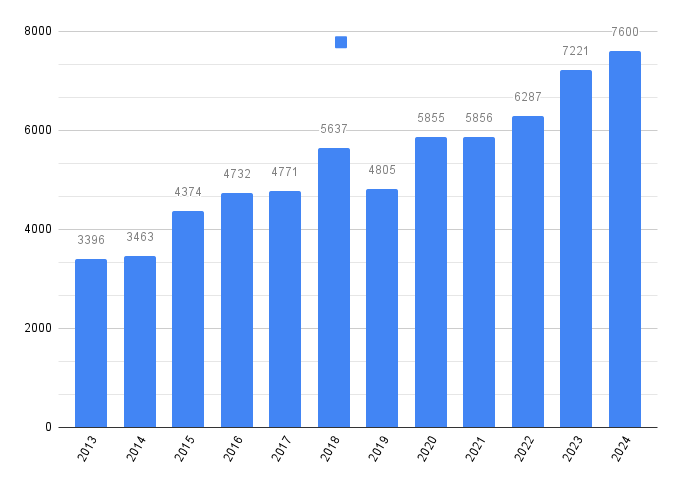

Getting better at running is pretty difficult, but not that complicated. For all the talk of quality vs. quantity, recovery tools and double thresholds, we cannot ignore the most basic data. I’m not one to overuse data in training. I believe that communication between the athlete and the coach remains the most important indicator of where you are at in training. But one of the benefits of this new era of wearables, is that we can have a very clear image of the big picture. As I have worn a GPS watch since the very start of my career, I now have a summary of 12 years of training. I made a little bar graph and here’s what I’ve got out of it. It doesn’t look like much, but this graph has dominated the past decade of my life.

Obviously, it is too simplistic to attribute better running performance only to increased running volume, but I think the correlation cannot be ignored. I think there’s not a better predictor for actual running performance. So, while it doesn’t paint the whole picture, the training volume does provide the framework, on which to build specific training.

In my own case, my training volume reveals my commitment to the sport, and reflects quite accurately the performance gains I made throughout my career. It starts simple. Between 2013 and 2016, I got better by increasing my mileage steadily every year. The results followed, and I qualified for my first European Cross Country Championships in 2016. Between 2016 and 2019, I got better, but not significantly. In retrospect, I probably became less hungry, and I stagnated a bit. When the covid-lockdown hit, I started to train more seriously, because we had all the time in the world. When we were allowed to race again, it showed. In a year and a half, I reinvented myself in training and in races, and qualified for European and World Championships left and right. I got to the level where I was at a crossroads. I was working part-time as a physical therapist, but with the Paris Olympics ahead, I decided to quit my job, go all-in on a new event, and start training for the Marathon. A new coach, altitude training camps and more time for rest. This new training structure had to give me the extra little push I needed to make it to the Olympics. It required deliberate choices in my life to get there. The amount of training needed to compete at the Olympic level, requires a very specific lifestyle. The easy part is the actual training. It gets tough when you’re setting up your life to prioritize rest and serenity. Being content with a simple life with lots of structure. I like that type of life, but you have to actively work on it, because our society encourages us to take on everything all at once.

These numbers reveal the best advice I can give to novice runners. If you want to get better at running, or any other skill for that matter, you have to spend more time doing it. Simply put: Run more. Don’t overcomplicate your training, but do lots of it! We tend to underestimate the amount of time needed to develop a skill. I believe that my biggest talent is patience. I only started to perform internationally in 2021. I had been running for 8 years at that point. Only after 10 years did I become good enough to think about making the Olympics. During all those years, I kept investing more time and energy into running, believing that eventually I’d reach the highest level. I’m really curious to hear from people that believe that high volume is overrated for a long distance runner. In my mind, it just doesn’t make any sense.